Design decision: why do we need the stale closure problem in the first place?

See original GitHub issueHi,

I initially asked this on Twitter and @gaearon suggested me to open an issue instead. The original thread is here: https://twitter.com/sebastienlorber/status/1178328607376232449?s=19 More easy to read here: https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1178328607376232449.html But will try to make this issue more clear and structured about my args and questions.

Don’t get me wrong, I really like hooks, but wonder if we can’t have smarter abstractions and official patterns that make dealing with them more easy for authors and consumers.

Workaround for the stale closure

After using hooks for a while, and being familiar with the stale closure problem, I don’t really understand why we need to handle closure dependencies, instead of just doing something like the following code, which always executes latest provided closure (capturing fresh variables)

Coupling the dependencies of the closure and the conditions to trigger effect re-execution does not make much sense to me. For me it’s perfectly valid to want to capture some variables in the closure, yet when those variables change we don’t necessarily want to re-execute.

There are many cases where people are using refs to “stabilize” some value that should not trigger re-execution, or to access fresh values in closures.

Examples in major libs includes:

- Formik (code is pretty similar to my “useSafeEffect” above): https://github.com/jaredpalmer/formik/blob/master/src/Formik.tsx#L975

- React-redux, which uses refs to access fresh props: https://github.com/reduxjs/react-redux/blob/b6b47995acfb8c1ff5d04a31c14aa75f112a47ab/src/components/connectAdvanced.js#L286

Also @Andarist (who maintains a few important React libs for a while):

We often find in such codebase the “useIsomorphicLayoutEffect” hook which permits to ensure that the ref is set the earliest, and try to avoid the useLayoutEffect warning (see https://gist.github.com/gaearon/e7d97cdf38a2907924ea12e4ebdf3c85). What we are doing here seems unrelated to layout and makes me a bit uncomfortable btw.

Do we need an ESLint rule?

The ESLint rule looks to me only useful to avoid the stale closure problem. Without the stale closure problem (which the trick above solves), you can just focus on crafting the array/conditions for effect re-execution and don’t need ESLint for that.

Also this would make it easier to wrap useEffect in userland without the fear to exposing users to stale closure problem, because eslint plugin won’t notice missing dependencies for custom hooks.

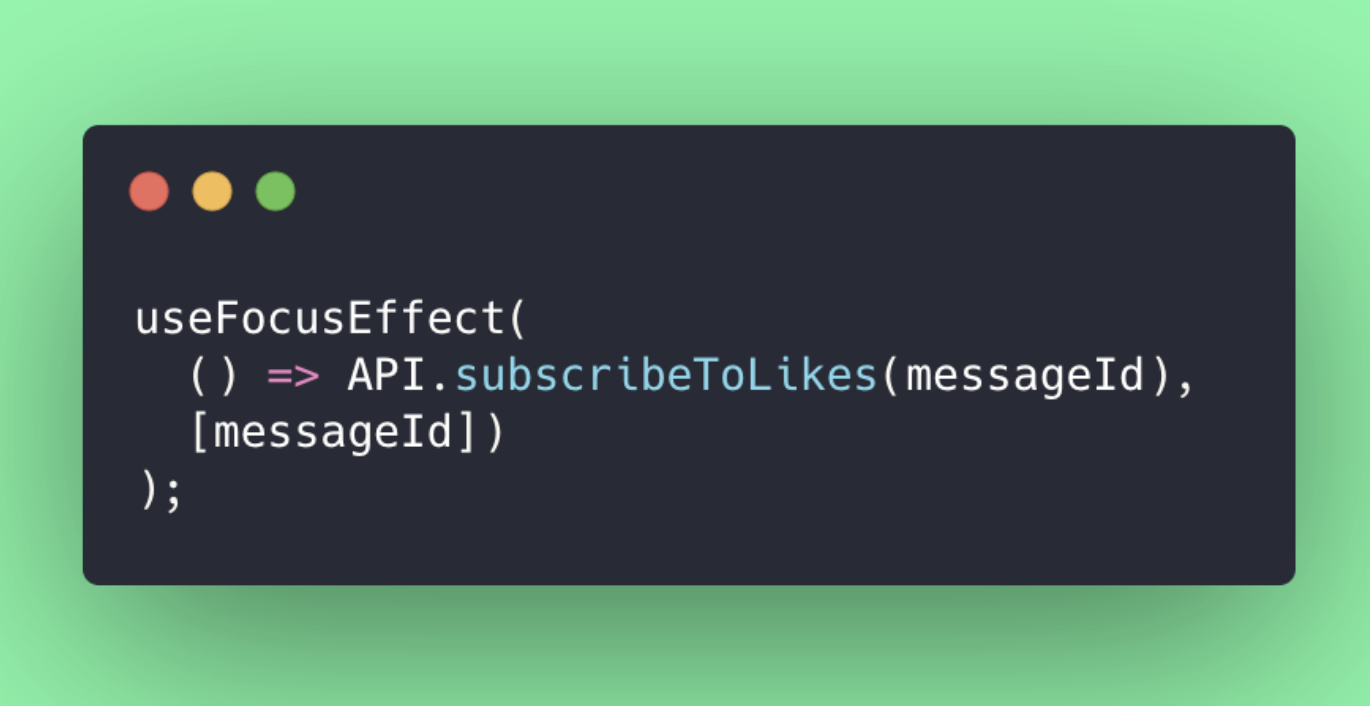

Here’s some code for react-navigation (alpha/v5). To me this is weird to have to ask the user to “useCallback” just to stabilize the closure of useFocusEffect, just to ensure the effect only runs on messageId change.

Not sure to understand why we can’t simply use the following instead. For which I don’t see the point of using any ESLint rule. I just want the effect to run on messageId change, this is explicit enough for me and there’s no “trap”

I’ve heard that the React team recommends rather the later, asking the user to useCallback, instead of building custom hooks taking a dependency array, why exactly? Also heard that the ESLint plugin now was able to detect missing deps in a custom hook, if you add the hook name to ESLint conf. Not, sure what to think we are supposed to do in the end.

Are we safe using workarounds?

It’s still a bit hard for me to be sure which kind of code is “safe” regarding React’s upcoming features, particularly Concurrent Mode.

If I use the useEffectSafe above or something equivalent relying on refs, I am safe and future proof?

If this is safe, and makes my life easier, why do I have to build this abstraction myself?

Wouldn’t it make sense to make this kind of pattern more “official” / documented?

I keep adding this kind of code to every project I work with:

const useGetter = <S>(value: S): (() => S) => {

const ref = useRef(value);

useIsomorphicLayoutEffect(() => {

ref.current = value;

});

return useCallback(() => ref.current, [ref]);

};

(including important community projects like react-navigation-hooks)

Is it a strategy to teach users?

Is it a choice of the React team to not ship safer abstractions officially and make sure the users hit the closure problem early and get familiar with it?

Because anyway, even when using getters, we still can’t prevent the user to capture some value. This has been documented by @sebmarkbage here with async code, even with a getter, we can’t prevent the user to do things like:

onMount(async () => {

let isEligible = getIsEligible();

let data = await fetch(...);

// at this point, isEligible might has changed: we should rather use `getIsEligible()` again instead of storing a boolean in the closure (might depend on the usecase though, but maybe we can imagine isEligible => isMounted)

if (isEligible) {

doStuff(data);

}

});

As far as I understand, this might be the case:

So you can easily get into the same situation even with a mutable source value. React just makes you always deal with it so that you don’t get too far down the road before you have to refactor you code to deal with these cases anyway. I’m really glad how well the React community has dealt with this since the release of hooks because it really sets us up to predictably deal with more complex scenario and for doing more things in the future.

A concrete problem

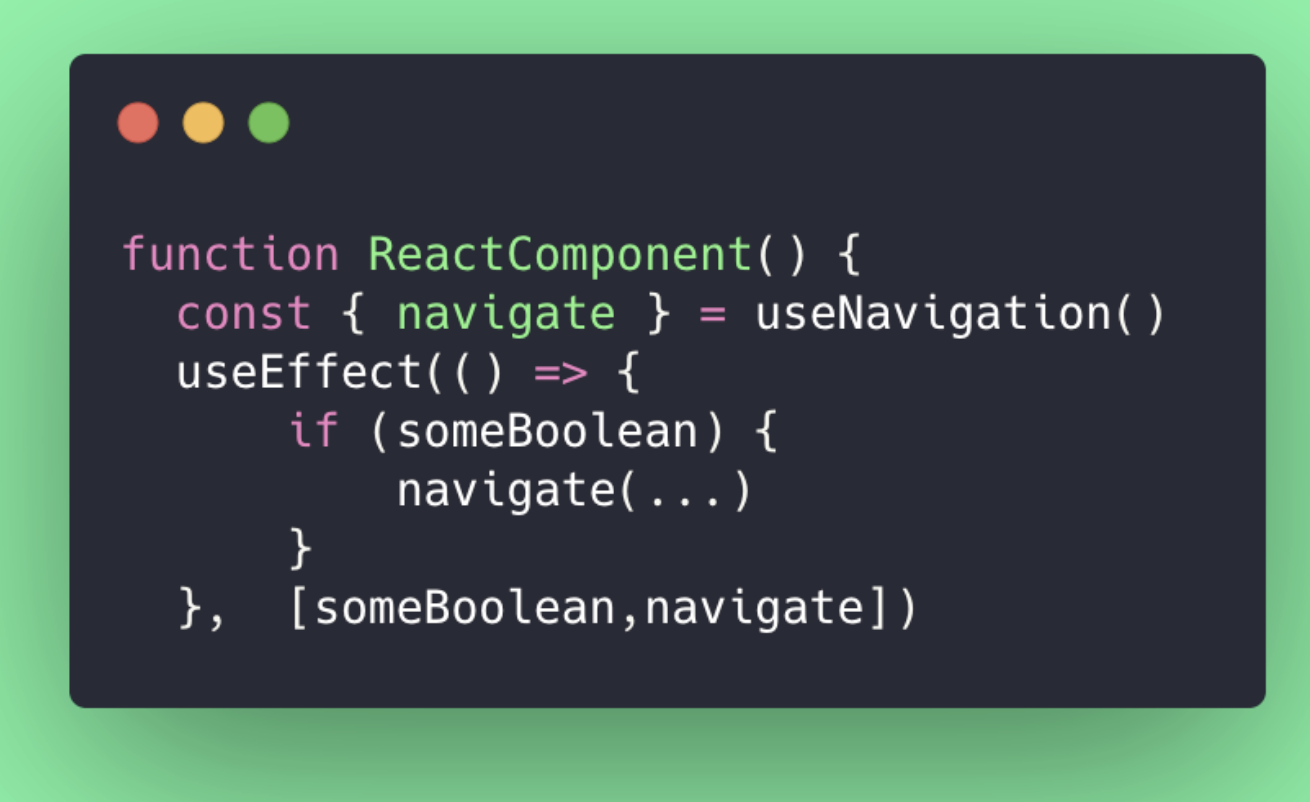

A react-navigation-hooks user reported that his effect run too much, using the following code:

In practice, this is because react-navigation core does not provide stable navigate function, and thus the hooks too. The core does not necessarily want to “stabilize” the navigate function and guarantee that contract in its API.

It’s not clear to me what should I do, between officially stabilizing the navigate function in the hooks project (relying on core, so core can still return distinct navigate functions), or if I should ask the user to stabilize the function himself in userland, leading to pain and boilerplate for many users trying to use the API.

I don’t understand why you can’t simply dissociate the closure dependencies to the effect’s triggering, and simply omitting the navigate function here:

What bothers me is that somehow as hooks lib authors we now have to think about whether what we return to the user is stable or not, ie safe to use in an effect dependency array without unwanted effect re-executions.

Returning a stable value in v1 and unstable in v2 is a breaking change that might break users apps in nasty ways, and we have to document this too in our api doc, or ask the user to not trust us, and do the memoization work themselves, which is quite error prone and verbose. Now as lib authors we have to think not only about the inputs/outputs, but also about preserving identities or not (it’s probably not a new problem, because we already need to in userland for optimisations anyway).

Asking users to do this memoization themselves is error prone and verbose. And intuitively some people will maybe want to useMemo (just because of the naming) which actually can tricks them by not offering the same guarantees than useCallback.

A tradeoff between different usecases in the name of a consistent API?

@satya164 also mentionned that there are also usecases where the ESLint plugin saved him more than once because he forgot some dependency, and for him, it’s more easy to fix an effect re-executing too much than to find out about some cached value not updating.

I see how the ESLint plugin is really handy for usecases such as building a stable object to optimize renders or provide a stable context value.

But for useEffect, when capturing functions, sometimes executing 2 functions with distinct identities actually lead to the same result. Having to add those functions to dependencies is quite annoying in such case.

But I totally understand we want to guarantee some kind of consistency across all hooks API.

Conclusion

I try to understand some of the tradeoffs being made in the API. Not sure to understand yet the whole picture, and I’m probably not alone.

@gaearon said to open an issue with a comment: It's more nuanced. I’m here to discuss all the nuances if possible 😃

What particularly bothers me currently is not necessarily the existing API. It’s rather:

- the dogmatism of absolutely wanting to conform the ESLint rules (for which I don’t agree with for all usecases). Currently I think users are really afraid to not follow the rules.

- the lack of official patterns on how we are supposed to handle some specific hooks cases. And I think the “getter” pattern should be a thing that every hooks users know about and learn very early. Eventually adding such pattern in core would make it even more visible. Currently it’s more lib authors and tech leads that all find out about this pattern in userland with small implementation variations.

Those are the solutions that I think of. As I said I may miss something important and may change my opinions according to the answers.

As an author of a few React libs, I feel a bit frustrated to not be 100% sure what kind of API contract I should offer to my lib’s users. I’m also not sure about the hooks patterns I can recommend or not. I plan to open-source something soon but don’t even know if that’s a good idea, and if it goes in the direction the React team want to go with hooks.

Thanks

Issue Analytics

- State:

- Created 4 years ago

- Reactions:165

- Comments:28 (13 by maintainers)

Top Related StackOverflow Question

Top Related StackOverflow Question

There’s a bit to unpack here and your original comment doesn’t quite line up with how I see this progression so I’ll respond in a different format so pardon me if I don’t answer some questions directly.

This is very fair feedback and a general pain point people have right now. In fact, this is basically Vue’s whole point with their version of Hooks to support mutable containers being captured by closures. It’s a valid approach but it does cause a lot of downstream effects. So we’re hoping we can achieve a different approach over time.

Not Just Closures

Let me first point out that (same as in classes), this is not limited to closures. The same thing happens with objects too.

This captures stale data in the same way as closures do.

The difference is that closures might be a bit more opaque. You might be able to do a shallow comparison on an unknown object but it happens there too.

It just happens that there are common patterns that happen to use closures as the most idiomatic API. It’s possible that these patterns can be redesigned to avoid closures.

Composability

The most common way this happens is by passing something through props. This creates a copy of the value. This decoupling is how we are able to create many composable abstractions. It is very common and idiomatic in React so we can’t dismiss that this is going to be the most common form. This has indirect downstream effects because if you can’t rely on mutation propagating in one intermediate level, you can’t rely on it deeper neither.

The primary goal of React’s API is to define an API boundary between abstractions. A common language that has certain properties that you can rely on. That’s why it’s important that it’s clear when certain values have certain properties. E.g. refs provide a common language to talk about a “box” that may contain mutable values for interop with imperative systems.

If a Hook isn’t responsive to new values, that break such a contract. So in general, it would be a bad idea to let that pattern spread.

useEventCallback

The useEventCallback concept is basically something like this:

I actually came up with this very early in the process, before Hooks was a thing.

However it has some bad qualities that lead me to want to strongly discourage this pattern.

useEffect is not always safe because there’s a potential gap between commit and useEffect. Many people know that, but what people don’t know is that useLayoutEffect also isn’t completely safe because sometimes these callbacks are used by other effects deeper in the tree that fire first.

useLayoutEffect(() => props.onCallback());and this will have the stale value in this case but a plainuseCallbackwouldn’t. So if this was a built in Hook, React would use a different phase to update it.In Concurrent Mode, we try hard to move as much as we can out of this critical “commit” phase. E.g. as much as possible should move to effects that don’t block paint (

useEffect) or the render phase which is async. This approach moves it to be synchronously blocking. This is probably mostly fine if this is a rare pattern. Once it is used everywhere, then it means that large updates will have a large synchronously blocking phase which undermines the responsiveness of the concurrent system.“Callbacks” in React are used in two ways. Either as a pure function during render or as part of a reducer, or an imperative method used as event handlers with side-effects. E.g. render props. Currently, simple functions and

useCallbackcan be used for either. We’d need to be very clear that these functions cannot safely be called during render and separate the pure ones from the event callback ones. If this was a worth while strategy this could be doable.If this was the only way to solve things, then we should adopt this upstream but I don’t think this is ever actually the best solution available. So let’s see what else we can do.

Keep Imperative Code Separate

I’d argue that the

useEventCallbackpattern is actually not necessary in general. It comes from using React state where you could be using refs.If you get into this situation it’s not because you have a nice purely functional model. It’s because you have interop with imperative code and that code likely relies on subtle mutation anyway so it’s not suitable to mix with React’s deferred/batched/concurrent state.

E.g. imagine if your callback was using state like this:

This is probably not great anyway since the setState can be batched and deferred so it might not update the second callback immediately.

If this instead used a ref then it wouldn’t get invalidated all the time:

Using a ref and imperative code is discouraged if you can avoid it, but if you’re writing imperative code anyway then this might be the best way to solve it.

In this code,

useCallbackis sufficient because it won’t invalidate as often as if the state was also captured there.I think the issue is that React doesn’t really make it easy to tell when you’re entering imperative code and should be using a ref vs not. Also, it’s not easy to read a ref in a render function easily. We have some work to do there.

Referential Identity == Best Practice

It seems to me that this is a natural evolving best practice just like other performance considerations. In libraries that work on the mutation model, you also have to think about if you’re returning a reactive value that has its origin traced in an efficient way or if it’s a derived copy that will be reevaluated.

I think we can do a lot more to make this automatic, but not if you’re using patterns that aren’t optimizable by us. For example, the useRef + useCallback pattern above is describing semantics that are easily optimizable in our current approach. Similarly passing down a stablee dispatcher instead of a callback that closes over state is best-practice that helps avoid the perf problems to begin with.

Strict Lint Rule

I think this is actually quite important. We constantly get questions about why something didn’t work and it’s almost always because someone decided to break the rules in one place and the consequences snowballing elsewhere and then it’s too late to refactor the code. It’s really hard to know that it is safe to break it.

However, the strictness also is about promoting patterns that are automatable. The lint rule is just the first step. The next step we added was “autofixing” that added dependencies for you.

The next step is adding a compiler that adds all the memoization for you in the entire app. That way you don’t have to think as much about

useCallbackanduseMemobecause we can infer it. I believe that this will alleviate a lot of the pain points since as a lib author you don’t necessarily have to think about adding them, and you can assume that updates are much more fine grained in the system in general.However, this can only automate what you’re already expressing today. So if today’s code isn’t working then we need to either change our patterns, or shift the approach used by React. Breaking the rules, isn’t just a convenience, it means that automation isn’t safe.

I’m a little skeptical of this. It seems like you’re saying that it’s okay for certain values that your function operates on to be totally arbitrary. Can you provide a couple of concrete cases when this is true?

This is a really long GH issue, but I wanted to respond to this particular question. There is a potential serious bug when it come to using effects and refs to wrap closures, given React’s current hooks primitives.

First, here’s the similar pattern I’ve seen used (within Facebook too):

This has a pretty serious flaw if you were to ever pass the callback it creates as a prop to a child component. For example:

Note that

useEffectSafeshown in the issue description above usesuseEffect. This is okay since it’s self contained, but if you were to useuseEffectfor a generic callback wrapper- it would be even more likely to trigger a bug like the one above- since alluseLayoutEffectfunctions would run beforeuseEffectupdated the ref.I think that implementing a hook like this correctly would require React to add an API like

useMutationEffect(see #14336).